|

NOTES re: Journals ~ LIMBERING THE WRITING MUSCLE |

Getting Started: JOURNALS AND FREE WRITING

Introduction to any composition/writing course: Some key Information: (In Latin, com = together and pose = place or position)

Composition: What it is and why we study it: Human interest in the patterns that ideas, sounds, and words, etc., can take is older than most of us can even imagine. Simply, the order, or sequence of things we do, or say is a basic kind of composition, whether that order seems intentional or not. The study of composition (to compose) in writing is, then, the study of various patterns of ideas/words and how they can present and communicate messages. Finding patterns helps us understand many aspects of our world. Studying the arrangement of ideas ( in writing or speech) and how those patterns can be used as tools in communication, is an important part of our general education.

INVENTION: Start before the composing/shaping:

Before writers address the basic shapes, patterns, formats or kinds

of essays, we probably

need to know what we want to communicate.

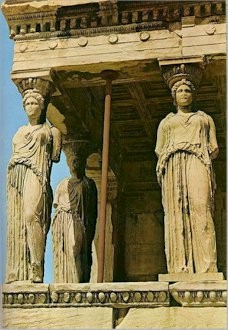

In classical Greek writings, where so many roots of our Western culture

can be traced, Aristotle's guidelines (canons) for composition (then

used mostly for oratory), still account for much of our current ideas about

good writing:.

need to know what we want to communicate.

In classical Greek writings, where so many roots of our Western culture

can be traced, Aristotle's guidelines (canons) for composition (then

used mostly for oratory), still account for much of our current ideas about

good writing:.

Classical rhetoric was developed to enhance the delivery of a good speech, and its purpose was to persuade the audience. In ancient Greek times, rhetoric was considered as one of the main subjects in Greek education, and the teaching and learning of rhetoric was recognized as a discipline. Aristotle's description of its structure reorganized the system of that rhetoric. After Aristotle, rhetoric was further developed by Cicero (106 - 43 B.C.) and Quintilian (35 - 96 A.D.). Among the five rhetorical canons [stages] (invention, arrangement, style, memory, and delivery), invention was considered the most important concept. However, throughout history, rhetoric has been diversely defined depending on the period and the rhetoricians. For a time, rhetoric even lost its logical character and was reduced to merely a consideration of style. The close relationship between rhetoric and speech lasted until the middle of the nineteenth century. As concern for effective writing began to grow, rhetoric was adopted as a way of structuring the written text. And invention once again began to be recognized as the most important of the five rhetorical canons. Rhetoric and composition as a discipline in the United States has been fully recognized in recent years. (Cho, chapter 3, paragraph 2) [Emphasis and link added]Though memory (in writing, at least) might now be called making a record of the idea pattern, the rest of the classical canons for structuring ideas have retained an identifiable function in today's courses in composition. But until quite recently, the the very first step in composing, invention, so important to the classical canon, was mostly ignored in modern composition classes. This stage was seen as suspiciously fanciful or even unnecessary as our culture insisted on cold reason, impersonal logic and scientific objectivity. Because this crucial first step of invention has not been routinely taught, until the last few years, most of us have had to deal with the frustration of the all-too-familiar, I don' know what ta write about! or Ideas only come to smart people, not to me. Well, those smart people probably just enjoy paying attention to their minds as they wonder about things, or find solutions to problems, etc. Often those people might be given to daydreaming, too often lost in thought, or some other disparaging description that reflects a scientific society's distrust of the imagination. Of course, inventors, scientists and mathematicians are vivid "imaginers" occupied by figuring out, even playing with, ideas. Paying attention to what our minds are presenting to us at any given moment, and searching for solutions to everyday problems, are things we all do, even if we're only partly aware of that process. When we pay attention to what we are thinking/imagining, we are interacting with ourselves and our ideas just as "smart" people do. Inventing (in Latin invenire, to come in), to allow ideas to come in, is, then, a process available to us all, if we allow the ideas to occur and pay attention to them!

So, journal writing and freewriting as well as clustering/mapping, listing,

etc., can help us to pay attention to what is occurring to us,

whether as a random free writing or journal entry, or as a tightly focused

exploration.. Our minds never stop giving us information. There is always

something going on in there; we just need to slow ourselves down and listen

to the images, memories, connections, wonderings, etc. that our minds are

always cranking out. If we close our eyes and think of a place we know,

the images are there, sounds, smells, emotions, ideas, all presenting tons

of information!

whether as a random free writing or journal entry, or as a tightly focused

exploration.. Our minds never stop giving us information. There is always

something going on in there; we just need to slow ourselves down and listen

to the images, memories, connections, wonderings, etc. that our minds are

always cranking out. If we close our eyes and think of a place we know,

the images are there, sounds, smells, emotions, ideas, all presenting tons

of information!

And that is why we will begin this course with an exercise that will

allow us to pay attention to our "mind's eye" and the process of thinking/imagining

that goes on all the time, waking or sleeping.

As an after-thought, it is interesting to note, here, that to amuse ourselves--as we all love to do--means that ( a = without + muse, a greek figure of inspiration or thinking) we are, literally, cutting ourselves off from our inner flow of ideas. Now, there is some food for thought...whenever we find a place where we can hear ourselves think! ;-)

Here is some information that may help get you started in journal writing, which will probably include some of each of the following types:

General Journals

A journal contains students' thoughts, feelings, and reflections* on various topics or experiences. Journal writing, a type of expressive writing, is used to explore ideas and to communicate with oneself. Journals provide students with a safe and risk-free place to reflect on personal thoughts and make connections between prior and new knowledge.

Personal Journals

In personal journals, students generally write about thoughts, feelings or experiences important to them. Personal journals are often used to introduce beginning writers to writing. The entries of emerging writers may contain more drawing than text.Response Journals

Response journals offer students the opportunity to respond in writing to a variety of texts. Students are encouraged to record their reactions to texts, exploring the relationships between texts and their own experiences or knowledge. Response journals are an excellent tool for connecting reading and writing. (The above definitions derived from: English Programs and Services Division, Prince Edward Island Department of Education)* Reflective Writing: The writer goes beyond a superficial presentation of facts. Evidence of reflection is apparent. The writer elaborates with examples, speculations and descriptions.

- Starting a journal is easier than you think. You may have already begun!

- Difficulty Level: Easy Time Required: 10-30 minutes

- Here's one way to start:

These journal links may be useful, too:

- In a blank book, or on a piece of notebook paper, [or on your computer] write today's date.

- Use ink rather than pencil. If you really prefer pencil, don't erase.

- Put the page number "1" somewhere on the paper, or number a few pages in the notebook.

- Make a short list of reasons you'd like to keep a journal.

- Briefly note your current interests, obsessions, worries, or projects.

- If you feel stuck, refer to things you've written lately: email to friends, to-do or shopping lists, office memos.

- Consider whether you want to cover everything or focus this journal on one aspect of your life.

- Write for a predetermined time, for as long as you feel like it, or until you're interrupted.

- Sign off, giving a moment's thought to when you'd like to write again. Schedule it, if that works for you.

Tips:

- Keep your favorite kind of pen with your notebook.

- Inexpensive materials can help you feel free to experiment.

- Your journal writing is for you. [But do be careful of recording things you really don't want read by someone else...]

- photos or drawings can be great additions

Journal Keeping | Writers Journal | Keeping a Journal | 10 Journaling Ideas | Starting a Journal

-

Freewriting is also a way to make

journal entries and generate/record thinking. Try this too, if it's new

to you!

Freewriting is also a way to make

journal entries and generate/record thinking. Try this too, if it's new

to you! - From: Elbow,Peter. Writing Without Teachers. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973. Print.

CHAPTER 1: FREEWRITING EXERCISES

The smallest level of all of the theory and practice contained in this book is the freewriting exercise. The idea in freewriting exercises

is to write for a short amount of time--about ten minutes in most cases--and simply to write whatever comes into your mind. But

even that description is not entirely accurate, since the whole idea of freewriting is to write without thinking. Perhaps a more

accurate description of freewriting is writing whatever comes into your pen. These exercises should be done at least three times a

week. There is only one requirement for freewriting: "that you never stop." In addition, this piece of writing will never be evaluated

in any formal setting (although, as you progress with these techniques, you may find yourself drawing on these informal sessions for material.)How Freewriting Exercises Help

When you write, you may have a certain amount of internal editing through which you must work before getting your ideas on paper. You have every voice, every piece of schooling, every other text you have ever read telling you how to write. While you may be able to manage the barrage of internal advice, you may also frequently find yourself paralyzed by the inability to negotiate that advice. In effect, you have so much advice, you find yourself staring at a blank page, or, often worse, writing a piece of text and scratching through it before you even know what you want to say.

Freewriting allows you to drop the internal editing and, if only briefly, write without stopping. As you progress with your practice in reewriting, you will become more and more accustomed to writing without the internal editing mechanism, and you will not find yourself forcing your language onto the page but rather, as with informal speech, saying what you have to say. This practice also helps your own individual voice come through your writing (a voice that can become stifled by too much internal editing).

>>>>><<<<<

More about freewriting: Freewriting Tips | Using Freewriting, Mapping, etc | More Peter Elbow-on generating writing

My grateful acknowledgement to the work of Peter Elbow, Pat Belanoff, Ken Macrorie, Toby Fulwiler, and Gabrielle Rico among others for the ground-breaking views and methodologies that have made the practice of writing a truly rewarding experience and tool for learning. JT

|

Copyright: Jane Thielsen - 2009 -all rights reserved |